Exemplar case: Donoghue v Stevenson

Photo by Richard Janda

For the initial project of the Legal Citation Lab, we picked Donoghue v Stevenson, the 1932 landmark decision of the House of Lords and likely the best known case in the common law, at least in countries belonging to the Commonwealth of Nations. The 3:2 decision in that case heralded the modern law of negligence, particularly that of consumer products liability, and continues to be cited nearly a century later.

Background

The case originated in Paisley, Scotland, where Ms May Donoghue and an unnamed friend met for refreshments at the Wellmeadow Café. The friend ordered and paid for a “pear and ice” for herself and a Scottish float—ice cream and ginger beer—for Donoghue. The float was served unassembled: the ice cream in a glass and a bottle of ginger beer on the side. The bottle was of brown opaque glass, so that its contents couldn’t be seen until poured out. The bottle was labelled “D. Stevenson, Glen Lane, Paisley.” Francis Minghella, Wellmeadow’s proprietor, poured some of the ginger beer onto the ice cream and Donoghue ate from the float. Her friend then poured more ginger beer onto the ice cream, and from the bottle emerged the partially decomposed remains of a snail. Donoghue became ill both from what she was and what she fears she had already eaten. She saw her doctor and was admitted to the Royal Glasgow hospital for further treatment, eventually recovering.

Photo by Richard Janda

Or so say the pleadings of the case. We’ll never actually know whether there was a snail in the ginger beer, the identity of the friend, or many other facts about the case. That’s because it proceeded, first through the Scottish courts and then to the House of Lords, on a pure question of law: assuming the allegations to be true, did the pursuer (plaintiff or claimant) have a recognized cause of action against the defender (defendant), Mr. Stevenson?

Stevenson’s involvement arose because Donoghue had a difficult legal problem in suing Minghella, the proprietor of the Wellmeadow Café. First, she had no contract with Minghella, under which he could be said to have guaranteed the ginger beer fit for consumption. Any contract that existed was between Minghella and Donoghue’s friend, who had ordered and paid for the drinks. Second, Minghella had neither done nor failed to do anything that could be construed as negligent. The ginger beer bottles had come to him sealed with the intention that they remain that way until sold to consumers and the opaqueness of the bottles prevented him from inspecting the contents before serving the ginger beer.

Success for Donoghue therefore hinged on making out a case against the only remaining player, Stevenson, the manufacturer of the ginger beer. And the likelihood of making out such a case didn’t look good. Only a month before the pleadings were filed in Donoghue v Stevenson, the Scottish Court of Session had delivered its reasons for judgment in two conjoined appeals, styled as Mullen v Barr, both of which involved a dead mouse in a ginger beer bottle, though in those cases the ginger beer had been made by other manufacturers, not Stevenson. In those cases, decided 3:1, it was found as a fact that there were dead mice in the bottles, that the pursuers had consumed the ginger beer, and that this had caused their illness. A further finding was that the mice were in the bottles when they left the factories. In both cases, the manufacturers were able to show that their methods for cleaning bottles before filling them was the best in the trade, and that there had never been a similar incident over several decades of operation and the production of several million bottles of ginger beer. The pursuers in those cases were therefore unsuccessful.

This, then, is the context in which Donoghue v Stevenson proceeded. Donoghue pleaded that Stevenson had a duty “to exercise the greatest care [so] that snails would not get into [the bottles], render the ginger-beer dangerous and harmful, and be sold with the said ginger-beer” and that Stevenson’s bottle-cleaning system was defective in that “bottles were washed and allowed to stand in places to which it was obvious that snails had freedom of access from outside [Stevenson’s] premises, and in which, indeed, snails and the slimy trail of snails were frequently found.” Like the claimants in Mullen v Barr before her, Donoghue claimed £500 in damages, worth about £40,000 in today’s currency.

The judge at first instance, Lord Moncrieff, heard Stevenson’s arguments on duty of care on an interlocutory motion (a motion before the trial itself) and allowed the claim to proceed to trial. Observing rather that if the case were to be decided without reference to precedent, the question of law would have presented no “exceptional difficulty.” The precedent of Mullen v Barr, though, was significant, and it was only through a narrow and perhaps strained reading of that authority that Lord Moncrieff was able to find for Donoghue and allow the claim to proceed to trial.

Stevenson promptly appealed to the Second Division of the Court of Session. The four judges who heard the appeal were the same who had heard Mullen v Barr. Not surprisingly, the 3:1 split was the same, the majority holding that the only difference in the cases was that one involved a dead mouse; the other, a dead snail. With more than two years having passed since Donoghue had partaken of the Scottish float, she brought her further appeal in February 1931, and to avoid having to post security for costs, swore an affidavit testifying to her poverty-stricken status. The petition states that “the petitioner being very poor . . . is by reason of such her poverty unable to prosecute her Appeal, unless admitted by your Lordships to do in forma pauperis.”

The appeal was heard over two days in December 1931, and the five law lords who heard it “took time for consideration.” An unusually long time, for those days—some six months. We have no record as to what was said in oral argument, but the written argumentswere brief. Donoghue’s counsel, for example, cited only seven cases, and then only in passing. this style of argument was common, though one might have expected more appeals to principle and policy, especially for Donoghue. That this was not so suggests strongly that the majority judges—Lord Atkin and Lord Macmillan in particular—took up the cause on Donoghue’s behalf.

Lord Atkin framed the narrow issue as “whether the manufacturer of

an article of drink sold by him to a distributor, in circumstances which

prevent the distributor or the ultimate purchaser or consumer from

discovering by inspection any defect, is under any legal duty to the

ultimate purchaser or consumer to take reasonable care that the article

is free from defect likely to cause injury to health.” With that framing,

there is little hint of the great judgment that was to come—nothing,

for example, about duties of manufacturers to consumers generally or

about the “neighbour” principle that came to be associated with the

case. But Lord Atkin did not take long to get there. His speech begins

at p 578 of the Appeal Cases report; by p 580, after bemoaning the

wilderness of “particular instances” of duties created by the courts,

he set out his famous statement:

[T]here must be, and is, some general conception of relations giving rise to a duty of care, of which the particular cases found in the books are but instances. The liability for negligence . . . is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. But acts or omissions which any moral code would censure cannot in a practical world be treated so as to give a right to every person injured by them to demand relief. In this way rules of law arise which limit the range of complainants and the extent of their remedy. The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer’s question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law is my neighbour? The answer seems to be—persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.

Lord Atkin was operating from a shared knowledge base, citing “the lawyer’s question” about “who is my neighbour?” His reference is to the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Bible, in which a Samaritan came to the aid of a dying man, presumably, a Jew, when other Jews had refused to do so. By the end of the exchange with the lawyer, Jesus turned around the lawyer’s original question: instead of answering “who is the lawyer’s neighbour?” he asked “which of these do you think seemed to be a neighbour to he who fell among the robbers?” Of course, the one question cannot be fully answered without asking the other, and whole the point of the exchange is to get the lawyer to see that, which he does, as is apparent from his answer, “He who showed mercy on him.”

Lord Atkin also turned around the question or, more precisely, the answer to it, saying that the moral or religious rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes, in law, a rule that you are not to injure your neighbour. Moreover, he gave a “restricted reply” to the question “who is my neighbour?”—“persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in contemplation as being so affected when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions which are called in question.” This statement is one of the most important in the law of negligence, because it embeds two control devices: proximity and foreseeability. Proximity is inherent in the notion of persons “closely and directly affected;” foreseeability is inherent in the notion that a defendant ought “reasonably to have [the persons] in contemplation” as being directly affected by the defendant’s acts or omissions.

One problem, though, is that the two notions are linked together in a single sentence, such that it is hard to disentangle them. This linkage has both beguiled and bedeviled lawyers and judges ever since, and later developments of the law were criticized because, it was argued, some judges had misread Lord Atkin’s restricted reply. For example, in Anns v London Merton Borough Council, a particular formulation of the neighbour principle advanced by Lord Wilberforce was adopted in the UK and then in Canada, but subsequently overruled in the UK as being too expansionist and reinterpreted in Canada to narrow its scope.

Commentators on Anns said that Lord Wilberforce’s reading of Lord Atkin’s statement gave the impression that proximity is a function of foreseeability, whereas Lord Atkin meant proximity to be an independent criterion or brake on the concept of foreseeability. Contrary to what some of the commentators say, this is not clear from Lord Atkin’s famous statement, but it does emerge from his analysis of Heaven v Pender, when he explains that the principle advanced by Brett M.R. in that case was “demonstrably too wide.” The difference between the two judgments was that, under Brett M.R.’s formulation in Heaven v Pender, foreseeability alone sufficed to give rise to a duty of care; in Lord Atkin’s judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson, foreseeability was expressed to be in relation to persons “closely and directly affected.” Lord Atkin recognized that there would be cases in which it would be hard to ascertain when a relationship was or wasn’t sufficiently close or direct, but thought that the question wasn’t hard in this case. Showing some incredulity towards the arguments advanced by Stevenson’s counsel, he refuted them with a hypothetical:

There will no doubt arise cases where it will be difficult to determine whether the contemplated relationship is so close that the duty arises. But in the class of case now before the Court I cannot conceive any difficulty to arise. A manufacturer puts up an article of food in a container which he knows will be opened by the actual consumer. There can be no inspection by any purchaser and no reasonable preliminary inspection by the consumer. Negligently, in the course of preparation, he allows the contents to be mixed with poison. It is said that the law of England and Scotland is that the poisoned consumer has no remedy against the negligent manufacturer. If this were the result of the authorities, I should consider the result a grave defect in the law . . . . I would point out that, in the assumed state of the authorities, not only would the consumer have no remedy against the manufacturer, he would have none against any one else, for in the circumstances alleged there would be no evidence of negligence against any one other than the manufacturer . . . . [and then, a rhetorical appeal to a sense of innate justice] I do not think so ill of our jurisprudence as to suppose that its principles are so remote from the ordinary needs of civilized society and the ordinary claims it makes upon its members as to deny a legal remedy where there is so obviously a social wrong.

From there, Lord Atkin proceeded through a case-by-case demolition of precedents to show which accorded with his proposition and which didn’t, closing with a reference to Justice Cardozo’s majority decision in the US case of MacPherson v Buick Motor Company, decided 16 years prior—the case that was to form the basis for product liability law in the United States.

Lord Macmillan’s judgment focused more on one of the chief objections advanced by Stevenson’s counsel: namely, that Donoghue had no contract with Stevenson. From an earlier case, Winterbottom v Wright, this had been the stumbling block for claimants in one case after another. Lord Macmillan noted notes, first, that the existence of a contractual relationship between parties did not preclude other relationships, such as those in tort (delict). Accordingly, there was no reason why the same facts couldn’t give one party an action in contract and another in tort. Second, he said that the standard of the reasonable person should be used to determine whether a duty of care was owed in a novel case, and that “the categories of negligence are never closed.” Lord Macmillan thought it reasonable to conclude that Stevenson, as a person “who for gain [manufactures] articles of food and drink intended for consumption by members of the public in the form in which he issues them” should owe a duty of care to Donoghue. This was how Lord Macmillan saw the closeness and directness of the relationship; as to foreseeability, he also thought it was reasonably foreseeable that if Stevenson failed to take proper care, he might injure those persons whom he expected and wanted to consume his products. Of the neighbour principle there is no mention; it was this metaphor, adopted and shaped by Lord Atkin, that has resonated over time and has come to be synonymous with the case of the snail and the ginger beer.

With the case having established that Stevenson owed a duty of care to Donoghue, the ultimate consumer of the ginger beer, the matter was returned to the Scottish Court of Session for a hearing in which Donoghue would have had to prove the factual elements of the case that she had claimed, including that there had been a snail in the ginger beer, that it was there as a result of Stevenson breaching his duty of care, and that this snail had caused her illness. However, Stevenson died before the hearing, and his executors settled the case out of court in December 1934 for £200 of the £500 originally claimed.

Donoghue v Stevenson has come to be cited, relied on and reinterpreted in many other cases, including such landmark cases as Grant v Australian Knitting Mills Ltd [1935] UKPC 2 (extending manufacturers’ product liability throughout the Commonwealth of Nations), Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd [1963] UKHL 4 (opening negligence law to include claims for pure economic loss and negligent misrepresentation), and Home Office v Dorset Yacht Co Ltd [1970] UKHL 2 (public authority liability). In recent years, the case has been invoked both to support and deny claims about the existence of a duty of care in novel areas; for example, that an environment minister owed a duty of care to avoid climate change effects on Australian children when exercising powers to approve a coal mine expansion (Sharma v Minister of the Environment [2022] FCAFC 35); that a London shipping company breached a duty of care allegedly owed to workers employed by a third-party shipbreaking company in Bangladesh (Begum v Maran (UK) Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 326); and a proposed climate system damage tort against seven companies responsible for releasing greenhouse gas emissions (Smith v Fonterra Co-operative Group Ltd [2024] NZSC 5). Donoghue v Stevenson is also routinely cited in run-of-the-mill negligence cases as well as in cases having nothing to do with negligence, but referencing other principles such as the nature of legal precedent or the adaptability of the common law to changing societal conditions.

References & Further Reading

Chapman, Matthew. 2010. The Snail and the Ginger Beer: The Singular Case of Donoghue v Stevenson. London: Wildy, Simmonds & Hill.

Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] UKHL 100, [1932 AC 562] (British and Irish Legal Information Institute) or 1932 SC (HL) 31 (Scottish Council of Law Reporting).

UK CPI Inflation Calculator, https://www.officialdata.org/uk/inflation/1928?amount=500 (accessed 2024.08.08).

.jpeg)

Image generated by AI as prompted by John Kleefeld

Data Collection

The first stage of the project is to collect all available cases in which Donoghue is cited, directly or indirectly, by a court or tribunal when rendering a decision. This excludes cases in which Donoghue is cited by counsel in argument (where the report of the decision lists such cases) but isn't mentioned in the reasons for decision. Similarly, where a report’s editors annotate the case and include a reference to Donoghue, that case does not form part of the dataset unless the court also references Donoghue. To that extent, the dataset may be seen as under-inclusive, since citation by counsel or by law report editors is still evidence of Donoghue’s reach, as is citation by scholars in law review articles and books. However, the project focus is on judicial citation analysis, a field in existence for at least 150 years (Ogden, 1993), and for which methodologies have been developed through various studies, especially in the US but also in Canada (Alschner et al, 2024; Fournier, 2021, 2023; Neale, 2013; Warchuk, 2024). For something to count as a judicial citation, then, the criterion adopted for this project is that there must be some evidence of a court having considered Donoghue, even if only in a fleeting or formulaic way, or even if only declaring that Donoghue did not apply to the facts at hand.

Data Collection

On the other hand, the dataset may be seen as over-inclusive because it includes cases in which Donoghue does not appear in a list of cited cases at the beginning or end of a judgment, or in a table of cases judicially considered in a print reporter or citator. Often, such lists or tables do not show Donoghue as one of the cases cited in a law report, despite it being directly cited in one or more judgments in the report. In other judgments, Donoghue appears in a citation to another cited case. An example is Lord Wilberforce’s speech in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1977] UKHL 4, referencing the “trilogy” of House of Lords cases for the proposition that a prima facie tort law duty of care exists in certain situations. That passage has been widely cited, and is often followed by a discussion of the principles of proximity and foreseeability as expressed in Donoghue and other cases. Including such sub-citations casts a broader net than methodologies that return results based only on whether a case lists Donoghue as having been applied, followed, considered, distinguished, doubted or overruled (the terminology varies according to the methodology). The idea here is that to exclude Donoghue because it is cited only indirectly or because it has been distinguished or held not to apply would risk missing judicial treatment of the principles promulgated in the case. See, e.g., Landes et al, 1998 at 273 (in measuring influence, deciding not to differentiate among favourable, critical or distinguishing citations). This is also the philosophy behind AustLII’s LawCite project and is the approach used when noting up Donoghue in CanLII.

Therefore, as well as using the noting-up features of various legal databases, we also performed Boolean or text searches (e.g., “Donoghue NEAR Stevenson” or “[1932] AC 562”) and reviewed and reconciled the results with those obtained from citation searches using print resources or other digital resources that were available.

A research project of this scope—spanning the world and dating back to 1932—faces many challenges of access and coverage. Much of the world’s caselaw is still behind a proprietary paywall, and where public access exists through non-proprietary databases, coverage may be sparse. For instance, Singapore’s courts have been citing Donoghue since at least 1973, but a search on the Legal Information Institute databases yields only a few decisions dating from 2000 or later, depending on the court level. Through the generosity of the Singapore Academy of Law, we were able to close the gap with short-term complimentary access to its proprietary database, allowing us to generate a set of nearly 60 decisions from all levels of the Singapore courts. We had similar help from database providers in India and Africa.

Print reports have also been valuable, particularly for cases predating the 1990s, and work is still underway to identify and access relevant reports. In some cases, access to this law is now being addressed through the scanning and uploading of early print reports. For example, the Asian Legal Information Institute has uploaded scanned versions of early law reports from India and Burma (as it was then called), leading to the discovery of citing cases unavailable through other sources. The uploading of early print reports, and in some cases, typewritten judgments from court files, is a development that, while proceeding slowly, should aid those doing research such as is entailed by this project.

The lesson for those conducting citation analysis is that one must be creative and combine multiple search methods over multiple sources to ensure robust results when collecting cases.

Data Classification and Cleaning

We used Excel to populate the dataset, starting with CSV (comma-separated value) files downloaded from Westlaw in 2021 and comprising about 2200 cases citing Donoghue, chiefly from Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand. We supplemented this with electronic searches from 17 other proprietary databases, 33 Legal Information Institute collections; 130 court websites or other public-domain judgment portals; 90 print report series (not all of which were complete) and associated indexes or digests; and several secondary sources such as books and articles. As of mid-2025, the dataset had grown to over 5200 cases, with more being added monthly, albeit at a slower rate.

In the resulting spreadsheet, the citing cases are the unit of analysis; in other words, each case occupies one row of the spreadsheet, and the primary entry in a row is the case name. This includes individual instances of a case; if it proceeds through appeal, each instance is treated as a separate case for the purpose of the dataset.

However, there are many pieces of information about a case beyond its name, such as the date, jurisdiction, level of court, and citations to law reports in which the citing case appears. In a study that analyzed over 16,000 Israeli Supreme Court cases of all types over a specific period, the dataset had 61 variables, which gives a sense of how much information could be collected if one were inclined to do so (Weinshall & Epstein, 2020). The question becomes what additional data is manageable and useful for conducting citation analysis. For the initial dataset, we created fields for 16 data items. These are explained in the following table.

Click on the table to enlarge.

The following table provides an example of how the data fields have been entered for an individual citing case.

Dataset

This dataset originates from the Legal Citation Lab's Donoghue v Stevenson Citation Project, which examines the global judicial impact of the landmark 1932 House of Lords decision, famously known as the “snail in the bottle” case. As of mid 2025, the project has identified over 5,200 judicial decisions that explicitly cite Donoghue v Stevenson in court reasons, whether following, distinguishing, or otherwise engaging with the case. The data was gathered through an extensive review of worldwide legal repositories and databases, using Boolean searches, print law reports, and open-access and proprietary platforms. Structured in a tabular format, the dataset includes 16 key variables per case (e.g., jurisdiction, court level, and decision date). This rich, court-centred dataset enables advanced citation analysis, supporting both quantitative modelling and visualizations—such as time series, choropleth maps, and cumulative citation curves—to trace the enduring influence of Donoghue across common law jurisdictions.

Donoghue v Stevenson Global Citation Dataset © 2025 by Legal Citation Lab is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Data Visualization

One of the goals is to represent or visualize research results in ways that are informative and that lend themselves to further analysis. For example, the chart below shows the cumulative worldwide citations to Donoghue v Stevenson, classified according to court hierarchy.

Some of these methods can be interactive, such as the choropleth map below, which allows a user to hover over a country and see the number of citations to Donoghue v Stevenson for that country.

The interactive graph below illustrates the cumulative worldwide judicial citations to Donoghue v Stevenson by country or region. As the chart indicates, the rising number of citations reflects the case's growing significance and enduring impact over time. By hovering your cursor over a specific year in the graph, you can see the cumulative worldwide judicial citations to Donoghue v Stevenson for that particular year by country or region.

Data analysis and modelling

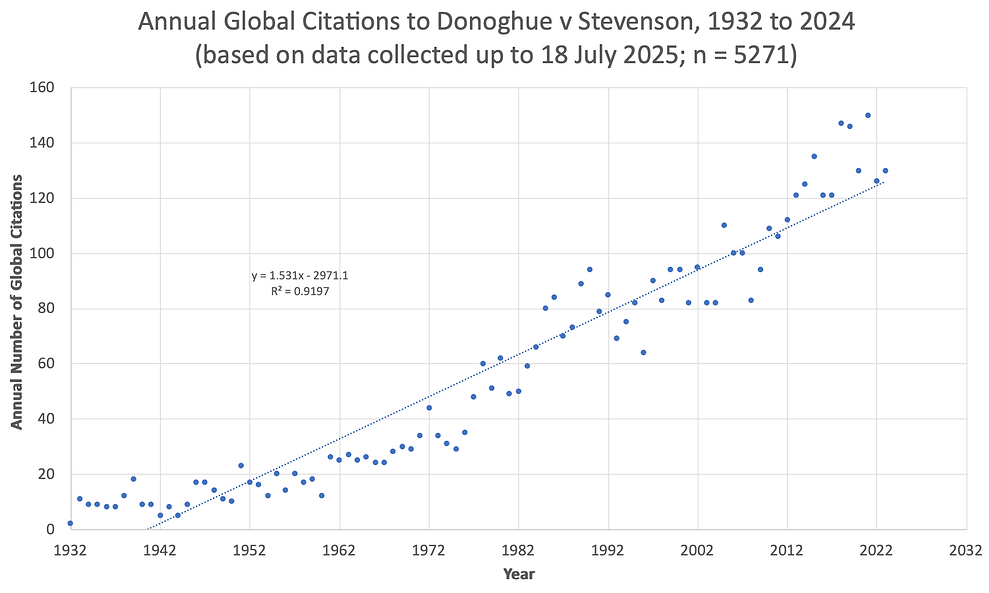

We may want to analyze or model the influence of a case, as reflected in judicial citations to it over time. A common starting point for such analysis is to graph a time series. Such a graph, also called a scatter plot, depicts data points at successive intervals of time, with each point correlating a time and a quantity being measured. The chart below, created using Excel’s Chart feature, does this by plotting the number of citations in the dataset (5271 at the time of writing) for each calendar year from 1932 to 2024. These are the blue dots in the chart. The data comes from the dataset’s Year field, as explained in Data Classification.

The graph suggests that the number of citations per year has been generally increasing, even if fluctuating from one year to the next. This intuitive observation can be modelled more precisely by fitting a trend line to the data using Excel’s trendline feature, the goal being to fit a line that best explains the existing data and that has strong predictive power. Is the trend linear (increasing at a steady rate), exponential (increasing at an increasing rate), logarithmic (increasing at a decreasing rate), or something else (e.g., increasing initially and then decreasing)? Excel can handle all these possibilities, but in this case, a linear regression, shown by the straight blue dotted line, appears to work well. The regression can be statistically tested for goodness of fit, and the slope of the line may be compared to the slope of similar trendlines constructed for other cases from different datasets, or for sub-components (e.g., individual countries) within the same dataset.

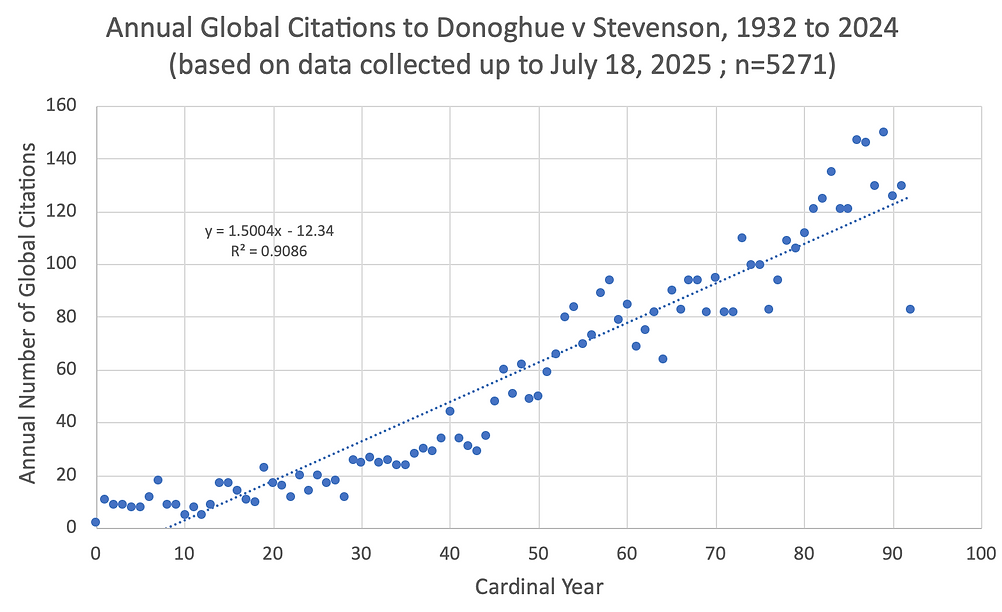

In contrast to the calendar-based view, the graph below uses cardinal dates to present the same citation data along a uniform time axis. Rather than mapping each point to a specific calendar year, this format treats each year as a consistent unit in a continuous sequence—ideal for emphasizing trends and patterns without the visual noise of irregular spacing or missing years. Each blue dot represents the number of case citations recorded in the dataset for that sequential position in time, from the first year (1932) through to 2024. This approach highlights the relative flow and density of citations over the years, based on the dataset’s Year field.

Qualifications

Any methodology has its limitations. Citation analysis is no exception, and some of these limitations, particularly around the collection of the data itself are discussed under Data Collection. There are also limitations that relate to the ways in which data is presented and analyzed.

One of these is that raw citation data alone tells only a limited story. For example, citations to a case may rise over time simply because overall court decisions rise. For more robust conclusions, we would need to know the changes in the citation rate over time, much as when reporting on crime rates or birth rates. This would require data on the number of court decisions in each jurisdiction by year, which could then be used to calculate citation rates: the numerator would be the raw citation count in a particular year; the denominator would be the number of decisions in that year. The time series would then plot the resulting citation rates for each year, rather than the raw citation counts. With some exceptions, such data is not readily available, though it may become more so as courts and data service providers become more aware of the uses of data analytics and legal informatics. Mathematical or statistical techniques may also be used to model the general rate of change of court decisions, the results of which could be used to derive an approximation of changes in citation rates over time.

Another limitation arises with choropleth maps. While their use is ubiquitous, they suffer from perceptual risks. This is because they implicitly incorporate a second variable, that being the area of the country, state, or other geographic unit. The area is represented in square kilometre, for example, shown by the size of each shape. As one blog post explains, even though on one level we know that a smaller shape doesn’t represent a smaller incidence of the data being studied, it looks like a smaller quantity; in a similar vein, we could be perceptually misled into thinking that the larger body of colour associated with a larger region means a larger incidence of the data being studied. This can be seen in the choropleth map for Donoghue v Stevenson, where the colour associated with USA and Brazil dominates that associated with Hong Kong and Singapore, even though those two countries have a lot more citations than the USA and Brazil. Other techniques, such as proportional symbol maps (also called “bubble maps”) may be used to address this problem, either as a supplement to, or substitute for, choropleth maps.